By Neale McDevitt

Whenever I interview a senior administrator for the first time, I do so with a little trepidation. These are busy people doing important work and, on occasion, some haven’t been too shy about dropping hints that they would rather be tending to their important work than talking to me. Those interviews tend to be short, curt and, safe to say, a relief to both parties involved when they’re over.

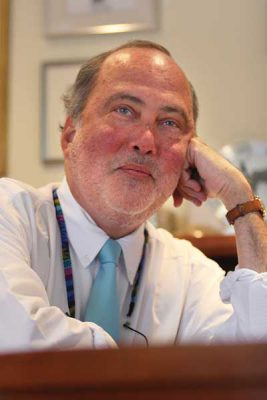

Few McGillians were busier or doing more important work than David Colman, Director of the world-renowned Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, when I first interviewed him for the McGill Reporter in 2007.

Wearing jeans and a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up, David met me with a firm handshake and a big smile as he ushered me into his office, asking if I wanted something to drink – coffee, juice or water. I declined all three, focusing on the task at hand.

I sat down, took out my recorder and laid my sheet of questions out in front of me, ready to conduct the interview. It was the last time I looked at the paper.

Miranda’s volcano

For the next 60-plus minutes, David and I just talked. Yes, he discussed work-related issues – The Neuro being named one of Canada’s first Centres of Excellence in Commercialization and Research; his tireless lobbying of the Harper government to expand the budget of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and, as I was to find out in later interviews, his favorite subject of all: his genuine admiration for talented people he worked with at the Neuro.

But we also talked things that weren’t on my little list. I spoke of my daughter Charlotte’s gymnastics and he chuckled about his daughter Miranda’s love of science fair volcanoes. We talked about parents, books, education and David’s 30-year love affair with the banjo. He was one of those rare people who was both interesting to listen to and interested in what you had to say.

Throughout our discussion David was funny, engaging, generous and self-deprecating – just a regular guy – who happened to be a brilliant scientist and the leader of one of the world’s great medical institutes. “I’m just a Jewish kid from the Bronx,” he told me, shaking his head and smiling like a guy who couldn’t believe his luck. “I’ve never really worked. I just took a hobby and made it into a career.”

Perhaps the thing that struck me most in our initial meeting – and confirmed with each subsequent interview – was David’s insatiable curiosity and his unflinching belief that the best scientists, and the kind he attracted to The Neuro, weren’t afraid to take risks. The thrill, he told me in a 2009 interview on the occasion of The Neuro’s 75th anniversary, is embarking on a journey with no set destination.

“Science is like the myth of Ariadne’s thread and the Minotaur’s labyrinth. We know where it will begin, but we don’t know where it will end,” he said. “[At The Neuro] we aren’t afraid to walk into the cave with our spool of thread. We may only get halfway and hit a wall. You can bang your head up against the wall for the next 20 years or you can back up and take another way.

“In a place like this where we rely on innovation, we don’t really know how things are going to turn out. If we knew, it wouldn’t be innovative.”

Quick to lend a hand

Last year, my wife and I had concerns about our foster daughter, who was having some serious cognitive issues at school. Very much on a whim, or perhaps out of desperation, I emailed David to ask his advice – knowing full well that he probably wouldn’t remember me from Adam.

But David answered right away, offering his support and sage counsel – like a friend would have done, even though it had been almost a year since we last spoke. I wrote him back, thanking him for his help and signing off with that old saying about it taking a village to raise a child. David replied in turn writing; “I think that in the old days when families were large, extended and lived close to each other, raising kids was easier and better for them. We need more kibbutzes! Let me know if you need anything else.”

When I heard the news of David’s untimely passing, it shocked and saddened me deeply on a personal level. Yes, The Neuro has lost its captain and the scientific world has lost one of its great champions. But that didn’t sink in until much later. All I could think about was how all of us had lost this intelligent, caring, down-to-earth man who was just looking to help. More than anything, David Colman was a good, decent man, and our kibbutz will be all the poorer without him.