Synthetic rink a boon to Hockey Research Group

By Jim Hynes

I used to skate like the wind, but now I’m more like a gentle breeze. Still, when professors David Pearsall and René Turcotte from McGill’s Ice Hockey Research Group invited me to try out the new synthetic skating surface in their lab at the Currie Gym building, I jumped at the chance.

Pearsall and Turcotte, professors in the Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, supervise work seven graduate students do on movement analysis and equipment research, including a number of hockey-related projects. Their biomechanics projects examine things like a person’s skating stride and other hockey skills such as shooting, while some of their equipment research evaluates the mechanical function of skates, sticks and protective equipment with respect to skill performance and safety. The work done by the group is funded in part by grants from both the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Bauer Hockey Inc.

In the past, the researchers in the group have had to rent ice time in local arenas or use a small sheet of polyethylene in the lab on which to conduct some of their hockey studies – a situation that was less than ideal. Ice time is expensive and the lighting in arenas isn’t sufficient for capturing movement using the motion-capture technology they sometimes employ. And they felt the small section of plastic on which their subjects were shooting pucks in the lab wasn’t realistic enough.

That issue was resolved last spring with the purchase of a 9-metre by 5-metre section of synthetic ice from Viking Ice, an Illinois-based manufacturer of synthetic skating rinks responsible for installations of various sizes from Las Vegas to Radio City Music Hall. Their product features a wood core covered by a ¼-inch thick polyethylene sheet on each side. The surface is regularly sprayed with a thin film of silicone lubricant that helps decrease friction. Thanks to synthetic ice, skating rinks can be installed (permanently or temporarily) in places like shopping malls or even parking lots for things like figure skating exhibitions or pleasure skating.

The surface at McGill cost approximately $15,000 and took about six weeks to install. Each side should last for about eight years; when one side is worn out the entire surface can be flipped over and skated on.

“It’s allowing us to do more realistic motion,” Pearsall said. “When we’re doing the shooting we’re not just standing, we can skate in now. So it gives more liberty to make it realistic to the subject.”

The new surface not only makes for a more realistic environment, it also gives greater weight to the data compiled in the studies conducted there.

“One of the things that David and I have been trying to do for many years is to have a controlled environment where we can characterize skating and shooting skills on the ice,” Turcotte said. “This provided us with a really realistic alternative where we can control the environment really well and we can be very precise. We’ve published a few papers already using data collected on it. We have a nice look at the kinematics of shooting for example. And we’re going to do the same thing with skating.”

Hitting the plastic

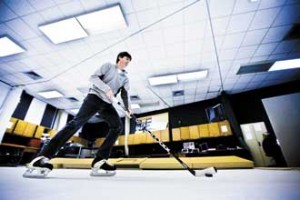

By the time I show up to the lab with my old skates and hockey-battered knees, somebody has already beaten me onto the “ice.” First-year Redmen defenceman Marc-André Dorion, a first team all-star with the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League’s Baie-Comeau Drakkar in 2007-2008, is skating in circles, trying to get the feel of the surface under his blades. His skates are fitted with instruments called strain gauges that measure the force he exerts while skating and he has electrogoniometres on his knees to measure joint motion and flex. The instruments send the data they collect back to a logger in a small backpack he’s wearing. Dorion is skating under the watchful eye of T.J. Stidwell, a student of Pearsall’s who is comparing skating kinetics and kinematics on ice and on this ice surface as part of his Master’s thesis. Once the work is done here in the lab, the same tests will be conducted on the real ice at the McConnell Arena.

“The hopes are that the results are essentially the same,” Pearsall said. “ If we can prove that this is a realistic environment to mimic those tasks, that gives confidence in anything else we do on the surface here for later studies.”

Dorion has finally been sent to the showers…now it’s my turn to hit the, er, plastic. I have to admit I was nervous about taking that first stride in front of a roomful of hockey scientists. I survive though, and after a few minutes spent just getting used to the strange new surface, I find the stride that helped make me a beer league scoring machine not too many years back. I even crank a few slappers just for the fun of it. Make no mistake, though, this is not ice. Skate blades don’t glide as quickly along it as they do on the cold stuff. But it’s a close enough approximation, and a good skater quickly learns to compensate for the added drag. You can do just about everything on this surface that you can on frozen water, including pivots, sharp turns and hard parallel stops. The only difference is that you send up a spray of shaved plastic, and not snow, when you do it.

For more information on McGill’s Ice Hockey Research Group, visit www.icehockeyscience.mcgill.ca