By Chris Chipello

Compassion, love, tolerance.

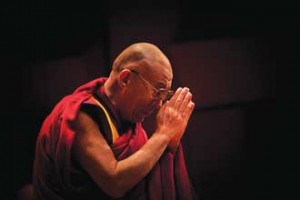

“Universal values” such as these, shared by the world’s religious traditions, underscore the essential fact that “we are the same human beings,” the Dalai Lama told 500 Education students from six Quebec universities gathered at McGill on Oct. 3.

Quebec’s recent introduction of an ethics and religious culture program in its school system was a key factor in the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader’s decision to include Montreal in his latest North American tour. He used his encounter with the future teachers to highlight the importance of ethical lessons for youngsters growing up in a world that too often confuses “material values” with “inner values.”

The Dalai Lama’s free-wheeling discourse in Pollack Hall was punctuated with Buddhist philosophy, Western science, impish humour and infectious laughter. As he noted at the outset, it also reflected a global view shaped by 50 years of living in India and traveling the world.

Billionaires, he has found, are often unhappy. Money and material goods bring physical comfort. But they also produce anxiety, stress and “problems.” Internal peace comes from caring, compassion, true friendships.

Ethics may be thought of as actions – physical or verbal – that bring some benefit to others, “especially in the long term.” And they aren’t necessarily linked to religious beliefs, the Dalai Lama said.

“The major portion” of the six billion people on Earth today are “not much serious about religion.” Some may feel they need pay no attention to religious values such as compassion and forgiveness. But independently of religion, “so long as you are (a) human being,” it’s important not to neglect universal values. Training in secular ethics can help cultivate these qualities.

Dialogue and mutual respect are keys to the pursuit of peace. Ecology should also be part of ethical education, since much of the damage to the environment is due to “man’s greed.” Children should be taught the importance of taking care of the planet.

Nor does secularism necessarily mean rejection of religion, the Dalai Lama maintained. In India, where multiple religions have coexisted for more than a thousand years, secularism has long meant respect for all religious traditions – and for non-believers. Without moral principles, on the other hand, religion can itself become “an instrument of exploitation.”

Responding to a student’s question about the importance of teaching religious culture, the Dalai Lama drew a distinction between religion and “religious culture.” One can embrace a culture, or way of life, coloured by a religious tradition, without personally adhering to that religion.

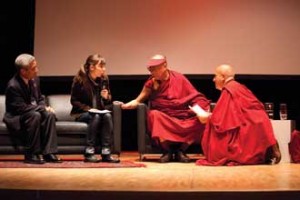

Peering out at the audience from beneath a red visor, the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize laureate sat cross-legged in his chair for most of the two-hour session. He spoke in English, with occasional help from Tibetan interpreter and McGill adjunct professor Thupten Jinpa. His remarks were translated into French by Matthieu Ricard, who trained as a scientist in France before becoming a Buddhist monk, and whose writings have made him something of an international celebrity in his own right.

Evoking Western interest in Buddhist philosophy, the Dalai Lama noted that Ricard, clad in flowing red robes, is “exceptional” in the degree to which he has embraced Buddhist ways: “His dress changed, everything changed,” he said, laughing. “But his face still remains European face.”

Some 500 of the 600 participants in the event were selected Education students from Université de Montréal, UQAM, Concordia, Bishop’s, Université Laval and McGill.

“You have made us all feel very special and fortunate as future teachers and you have reinforced in us the importance of human values and religious understanding,” said McGill’s Mitchell Miller, one of two students called on to thank the Dalai Lama at the end of the question-and-answer period. The Dalai Lama drew more laughter when he greeted Miller by stroking the student’s beard and observing: “Lot of hair!”

Turning serious again, the Dalai Lama offered a closing appeal to the hundreds of future Quebec teachers. “As soon as you wake up in the morning, think: my duty (is to) make some contribution for better world.” Many of the planet’s problems are “man-made,” and must be solved by people, beginning with “one individual, one family, ten families, hundred families, thousand families — then significant effect can come.”