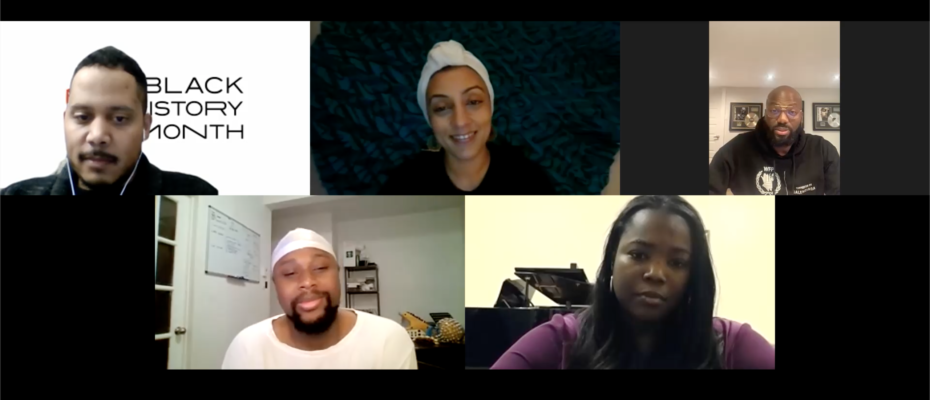

Blacks aspiring to make a career in music face a number of challenges, from their earliest forays into music as children and extending throughout their musical journey as adults. This was one of the takeaways of the panel discussion Black Perspectives: Artists Navigating Spaces on February 9.

However, panelists agreed that many obstacles facing Black musicians can be overcome, even circumvented, through mentorship, community connections and for Black artists and entrepreneurs to take literal ownership of their creative destinies.

Accessibility is a major hurdle for many Blacks when it comes to early exploration in music. “I came from the inner city [New York] where, in my neighbourhood, we didn’t have arts programs,” said Camille Thurman, an acclaimed jazz vocalist and saxophonist and an assistant professor of Jazz in the Schulich School of Music’s Department of Music Performance. “I literally got shipped across town an hour away to take music lessons.”

Thurman said even owning an instrument was something “my mother had to figure out, being a single parent.”

Always catching up

Several of the panelists, all accomplished artists or music entrepreneurs, spoke about feelings of always being behind.

“I’ve experienced this myself as a student where you get to the audition and the person is asking you to do something that you don’t understand – such and such a technique,” said Thurman. “The student feels ashamed because they don’t know – but they never even had a chance because they didn’t even get the tools to be able to achieve success.”

“A lot of times children are already disenfranchised from having access to the arts just based on their ZIP Code.”

“If we’re going have institutions where we bring people into addition, it is essential that we make those connections to the community, where there are programs that [offer] free access to music lessons, free programs in the summer.”

Sarah MK, a Montreal singer-songwriter, was pursuing health sciences when she decided to apply to the Vanier College Music Department as a vocalist. She aced the audition but struggled with the technical aspects of music. “I remember doing the theory test and just writing my name and leaving,” she said with a smile. “I was lucky enough to have remedial classes in the summertime and catch up. I’m always catching up.”

Diversity, community

These feelings of being behind are not as prevalent in certain local music collectives where collaboration and community are cornerstones to creating great music.

Sarah MK was one of the earliest members of the Kalmunity Vibe Collective, billed as “Canada’s largest and longest running improv collective best known for producing multiple weekly concerts.”

Kalmunity’s strength is its diversity. “Kalmunity really allowed us to connect with all the different cultures in Montreal,” said Sarah MK. “It also connected English and French and vocal artists and musicians. There were some musicians who were graduates from McGill and others who were self-taught. It’s a really beautiful place to meet up and create music together,” she said.

“I started going to Kalmunity when I was super young, probably about 12 or 13,” says Keita. “At that time, I didn’t even know that I was going to pursue a music career. I just knew that I liked playing music and these guys were playing on Tuesdays. Some of these people became my mentors over the years because I used to play next to them all the time and they would give me tips.”

Thanks in part to that mentorship, Keita honed his skills and gained confidence, playing at local events with Kalmunity, then touring with them, and, finally, collaborating with an ever-widening network of musicians. “I connected with people who allowed me to grow as a musician into the musician that I am today,” he said. “Mentorship is one of the most important factors – not only for music, but for anything in life.”

Connecting the dots

These collective experiences, with the emphasis on community and peer-support, are invaluable in the growth of the artist.

“When I was in university I was the person in my program who started the latest playing my instrument – and I started playing at 13. Some of these kids had started when they were four years old. They had been put into programs with some of the best jazz musicians in the country teaching them,” said,” said Keita. “Of course, when they get to university they’re killing it – and I’m just running to catch up to them.

“But the thing I had over them was I had this community that mentored me,” he said. “Your proficiency on an instrument isn’t really what gets you to bloom in the musical realm. What really makes you bloom is your ability to connect all the dots.”

Jazz ‘is about a way of living, a way of being’

‘Connecting all the dots’ is what Thurman would call the communal life of music – especially Jazz – a core aspect that is often inadvertently stripped away in an institutional setting.

“There is a disconnect a between where this music came from, this source – which is the community – and the institution. In one sense, the institution has created a space for the music to keep going. But at the same time, it has shifted the element of it being directly involved in the community,” said Thurman.

“When we talk about learning jazz, it is deeply rooted in the tradition of mentorship, and listening, and watching, and being in the moment, and learning how to work together. How do we survive in the moment?” she said.

“This is something that is beyond just a fact, beyond just a simple scale, and beyond just being able to repeat something and execute it perfectly every time,” said Thurman. “This music is about a function. It is about a way of living and a way of being.”

Circumvent the system

Often, the best way to circumvent these obstacles is for Black artists and entrepreneurs to establish their own spaces within which to create and promote their art.

“With urban music or Hip Hop, a lot of the artists are from Black heritage, Black culture. But the people who are working in the offices, making the decisions and deploying the capital are not Black,” said Koudjo, a music producer and an entrepreneur, who came to Montreal from his native Togo in 2000 to study economics at McGill. “Same thing in the media. Sometimes [there are people who] don’t even know the culture who are making decisions to play this music or that music, or to give access to this artist or that one. That was one of the main complaints I used to hear from artists.”

In 2018, with almost no Black-owned media outlets covering hip hop or rap, Koudjo co-founded QCLTUR (pronounced culture), a Montreal-based media platform that promotes arts and the culture. Much of the content being produced by QCLTUR are interviews of artists that are broadcast on social media.

Control the message, broaden the fan base

“The main goal was to promote Black culture and the culture that we consume,” said Koudjo. “And we want to make sure that the narrative of that culture is aligned with the culture [itself] – because there was a big disconnect from the artists that were big and selling music and packing concerts here in Montreal and the coverage that they had in mainstream media.”

QCLTUR’s success has not only helped increase exposure of Black artists among existing fans, it has helped grow the base.

“It allows us to be in spaces where we weren’t welcome three or four years ago,” says Koudjo. “This summer we were booked at Osheaga. We got to bring 23 artists with us on stage which is crazy because 95 per cent of them would never have had a chance to perform at Osheaga.”