Researchers at the RVH Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Lab spearhead new therapies to help stroke survivors move again

By Mark Shainblum

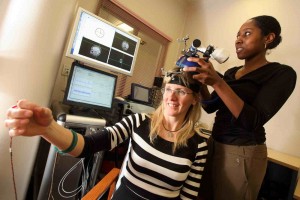

Dr. Lisa Koski is so blasé about being her own guinea pig that she doesn’t even stop talking as lab assistant Aisha Bassett places a plastic-covered magnetic coil against the left side of her head. A button is pressed, there’s a barely audible click, and Koski’s right arm twitches involuntarily. The effect is uncomfortably reminiscent of high school biology class and frogs on trays, but Koski swears she feels no discomfort and experiences no lasting effects from the demonstration.

Koski, an assistant professor at McGill’s Faculty of Medicine and a psychologist with extensive training in cognitive neuroscience, is director of the Royal Victoria Hospital Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Lab. She has just used her own brain to demonstrate a therapeutic technique called repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or rTMS. Her lab is spread over four spaces on the fourth floor of the RVH Ross Pavillion, just up the hall from patient rooms and physiotherapy facilities. Most of the high-tech TMS equipment is stacked in one corner of a single lab not much larger than a good-sized elevator.

“In rTMS we stimulate neurons in the brain with the stimulating coil,” Koski explained. “The coil generates a magnetic field which in turn induces a weak electric current in the brain cells near wherever you place it, in this case, the motor system.”

Koski specializes in neuropsychology, the study of the physical structure and function of the brain as it relates to specific psychological processes, behaviours and disorders. She did her Ph.D. at McGill, followed by post-doctoral research at UCLA specializing in TMS, where she helped set up that university’s first TMS lab.

“When I finished at UCLA, I got involved with a number of different projects, including some clinical work looking at brain function in people with strokes and other types of disorders,” she said. From there, it was a natural step to combine the two interests when she returned to McGill in 2004 and founded her current lab.

Originally developed in the late ‘80s as a safer, non-invasive alternative to electroconvulsive therapy for the treatment of depression, in recent years rTMS has also been shown to help sufferers of neurological disorders like migraines, Parkinson’s disease, dystonia and tinnitus. To date, however, there has never been a large-scale study of its potential benefits for stroke survivors. Koski and her colleagues are working to change that with the launch of an ambitious new clinical trial called ENHANCE.

“We’re primarily interested in treating motor impairments,” she explained, “particularly people who have difficulty moving their hands and arms after a stroke.”

Volunteer participants who take part in the ten-week ENHANCE study receive rTMS therapy followed by 90 minutes of standard physiotherapy administered by a therapist.

“In rehab what they do is training for different motor skills,” Koski said. “Sometimes the skill might be as fun and simple as eating popcorn with a hand that’s partially paralyzed, or other similar fine motor skills we’re trying to improve. We believe that rTMS treatments before physiotherapy will prime their brains and make them more responsive to the effects of the rehab training.”

Montreal-area residents who have suffered hand and arm mobility problems following a stroke are encouraged to participate in the ENHANCE study. For more information, please contact study coordinator Johanne Higgins at 514-934-1934 ext. 34420 or johanne.higgins@mail.mcgill.ca.