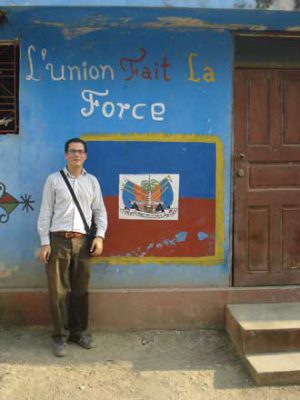

By Pierre Minn

Two weeks after the cataclysmic earthquake that struck Haiti on January 12, I returned to the city of Cap-Haïtien in the northern part of the country, where I recently completed fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork on international humanitarianism and medical aid. It was a bittersweet return – my trip had been planned long before the quake, and I had intended to present some of my research findings at the hospital where my research was based, and visit friends and colleagues. Instead, I arrived to find a country in shock, one that had only begun to mourn its enormous human, cultural and economic losses.

My initial relief at finding Cap-Haïtien relatively unscathed (northern Haiti sustained almost no damage or injuries from the quake) was tempered by the realization that nearly everyone here had lost family members and loved ones in the quake. Port-au-Prince is Haiti’s political, economic and social capital, and it has attracted people from throughout the country, making deaths there direct losses for families and networks on a national level. In the days that followed the quake, tens of thousands of homeless, injured and frightened people returned to their hometowns, relying on the dense support networks of kin and friendship that play such an important role in Haitians’ lives even in the best of times. Friends in Cap-Haïtien tell how their households of six or seven people have now expanded to thirteen or fourteen, as siblings, nieces, nephews, cousins, and friends come seeking shelter and solace. Families that had been struggling to survive on meager budgets must now stretch small meals even further.

As people stream in from the capital and other affected areas, local authorities have set up a processing center in the city’s gymnasium. Several organizations, Haitian and foreign, provide medical care, food, water, and a place to sleep for those who don’t have family in the area. Long lines form in front of the building, and while most people wait patiently in the baking sun, tempers flare and a sense of urgency grows. The weakest and most vulnerable – the injured, children and the elderly, are unable to hold their places in line. Further complicating the picture, desperately poor people from the surrounding areas have heard that food and medical care are being distributed, and add to the crowd of earthquake refugees. Given that those able to flee the destruction in Port-au-Prince are often among the healthiest and most resourceful of the victims, a classic dilemma emerges – what criteria should be used for determining who is a worthy recipient of aid? Should a young, healthy man from Port-au-Prince who lost his home and belongings in the quake have priority over a local sick, elderly woman who had no home and fewer belongings to begin with? These dilemmas and the politics of victimhood that shape them will only increase in the coming months.

Not long after my arrival, a physician friend calls me from Port-au-Prince, asking me to come translate for foreign medical teams at a field hospital. I find hundreds of patients recovering from amputations and orthopedic surgeries. They are the lucky ones, who reached medical care before dying of gangrene, blood loss, thirst, and other preventable causes. The patterns I observed among foreign aid workers during my doctoral research reappear here, albeit in intensified forms. Motivations for carrying out foreign aid are never simple or one-dimensional: compassion, the search for adventure, a desire to help, solidarity, wanting to collect war stories, curiosity… all of these and more are at play, even in a single individual. I am both inspired by the dedication and energy of the North American nurses and doctors and dismayed by the familiar pattern of foreign hero / Haitian patient-victim. Haitian medical personnel continue to work as they always have, in relative obscurity, with little access to the resources or visibility that could validate and nurture their skills and efforts.

When foreigners leave Haiti, they are often asked “Ou p ap tounen ankò?” (You won’t come back?) My twelve years of involvement here usually wasn’t enough to convince people that my time in the country would look any different from most foreign interventions: short-lived, often destructively so. Today, as I mentioned my upcoming return to Montreal, someone asked me for the first time, “W ap tounen byento?” (You’ll come back soon?). Their question, I suppose, reflects a hope for sustained efforts to collaborate with Haitians as they rebuild their country. These efforts need to be more thoughtful and transparent than previous ones. They must reflect a commitment to supporting the resilience, ingenuity and resourcefulness that have gotten the Haitian people through such difficult times in the past, and will help them overcome the formidable obstacles they now face.

Pierre Minn is a doctoral candidate in the Departments of Anthropology and Social Studies of Medicine at McGill.