On December 6, 1989, a gunman walked into a class at École Polytechnique, separated the men from the women and declared “I am fighting feminism” before beginning a 20-minute shooting spree targeting women. By the time the gunman turned his weapon on himself, 14 young women had been murdered.

The Reporter spoke to members of the Faculty of Engineering – a student, a professor and the Dean. Among other questions, we asked them about the challenges still facing female engineering students, the progress that has been made and the best way to honour the memory of the 14 women who were killed that horrible day.

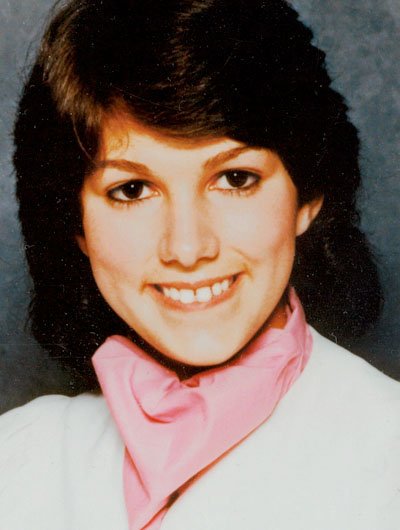

****

Like many undergraduate students, Taylor Lynn Curtis, is undecided on what she wants to do when she graduates from McGill in 2021. “Right now, I’m not entirely sure. I’m going through quite a few options,” says the fourth-year software engineering student minoring in political science. “I did an internship last summer in IT consulting and I really enjoyed it, so that’s a possibility. But I’ve also thought about launching my own company. It’s all very theoretical at the moment.”

No doubt she has heard the common refrain offered up by people of an older generation. “Don’t fret it. You’re young. You have your whole life ahead of you.”

Possibilities.

****

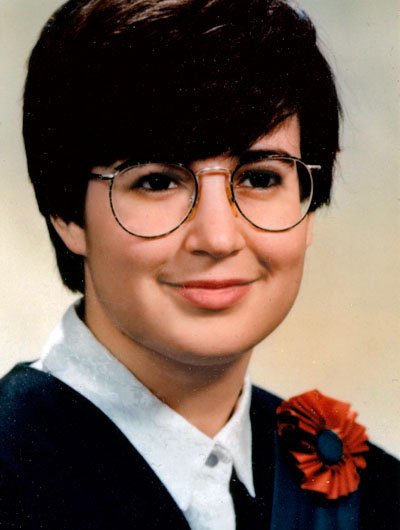

Thirty years ago, Geneviève Bergeron, a second-year civil engineering student at École Polytechnique and a talented clarinet player and choral singer, was also unsure of where her future lay, oscillating between a career in engineering and one in music.

But on December 6, 1989, Bergeron was murdered along with 13 other women – the worst mass shooting in Canadian history – and today all those possibilities remain forever unexplored.

****

When Jim Nicell was an Engineering undergraduate, the composition of his class was fairly typical for the time. “We were 110 students in my year. One hundred and nine men and one woman,” he says. “But nobody thought anything about it. That’s just the way it was.”

Nicell, now the Dean of Engineering at McGill, was doing his PhD at the University of Windsor when he heard the news about the shooting.

“It was traumatic. Absolute disbelief,” he says “I remember the incredible difficulty that I had in processing the whole thing and trying to understand why it happened.”

Nicell says that from the horror came a new awareness that gender inequality in the field could no longer be rationalized as “that’s just the way we do it.”

“It took time, but it created a sensitivity around these issues… So, why is it only one out of 110 students in my class was female? It started conversations. It provoked questions,” he says. What was it about the engineering culture that made it so challenging – even threatening – for women?

“Maybe that led to what’s happening now, which is a pretty big change in the gender balance in our profession.”

****

Viviane Yargeau, was a young student at the very beginning of her academic career in 1989. “After Polytechnique, the Cegep where I was studying created a scholarship to be awarded to a female student who was going to purse her studies in engineering. I had the honour of being the first recipient of this award,” says Yargeau, a professor in, and Chair of, the Department of Chemical Engineering. “I remember being really proud to be selected for the award but, at the same time, I would have preferred that the award did not exist.”

“For a long time, I had conflicting emotions about this award until I realized that encouraging females to study in engineering was a way to honour them. Since then, I have always been actively promoting opportunities for women in engineering.”

****

Curtis is the co-president of POWE (Promoting Opportunities for Women in Engineering), a philanthropic group under the Engineering Undergraduate Society (EUS). POWE was formed, albeit unofficially, just weeks before the tragedy at Polytechnique.

“At the time, POWE wasn’t actually registered because women in engineering wasn’t something that was talked about very much,” says Curtis. “It started as a bunch of students getting together in a very unofficial format.”

But the shooting changed everything. “That’s when people realized this is something that we actually needed,” she says. “In September 1990, POWE was ratified as part of the EUS in direct response to what had happened.”

****

POWE’s mandate is twofold.

First, it encourages girls and young women to consider a career in the field by exposing them to the many opportunities that an engineering degree offers. They do this by visiting high schools and Cegeps, and with the annual POWE Conference that brings some 100 female high school and Cegep students who are interested in STEM fields to McGill to tour labs and learn more about engineering.

Second, POWE supports McGill’s female engineering students through networking events, mentorship programs, workshops and industry tours.

“We strive to support and promote any woman who wants to wear an Iron Ring,” says Curtis. “We’re not only trying to get more people into McGill engineering, we also support them once they are here.”

****

While Nicell is proud of the strides being made in the Faculty of Engineering in terms of gender balance, he’s also a realist who understands that good intentions and a commitment to improve that balance are, to a certain extent, at the mercy of a system that is built to guard against sudden upheaval.

“We hire people with the idea that they will work at McGill for 35–40 years. So, the turnover is very slow,” he says. “There is an inherent lag in the overall system.”

“On the positive side, we’re making good progress, particularly at the assistant professor level,” he says.

In terms of the demographics of the student body, the ratio of women enrolled as Engineering undergraduates stands at about 30 per cent. “We’re moving in the right direction,” he says. “but there still is a lot of work to do, especially in certain disciplines that are traditionally very male dominated.”

****

For her part, Yargeau is very proud that Chemical Engineering has a higher representation of women at all levels (undergraduate, graduate and professors) than the norm.

As the first woman to hold a Chair in any department in the Faculty of Engineering, she hopes the improving demographics among students and faculty will attract more female students to engineering, no matter which discipline.

“A good way to honour the 14 women who were killed that day is to ensure that they are not forgotten, to fully acknowledge the reason why they were killed and to continue to actively promote engineering as a career for women,” says Yargeau.

****

“We can never forget that these 14 women were people. They had families and friends. They had dreams and plans,” says Nicell.

He is part of Engineering Deans Canada. To commemorate the Polytechnique tragedy, the group has launched the 30 Year Project highlighting 30 female engineering alumna across Canada who graduated within three years of the massacre and who have gone on to exceptional careers. One of the women highlighted is McGill alumna, former astronaut and current Governor General Julie Payette (BEng86).

“The idea is that by honouring the fulfilled potential of these 30 outstanding female engineers, we are also highlighting the lost potential of each of the women who were killed at École Polytechnique,” he says.

“Imagine where we’d be now if these women were still alive? On top of the great personal loss for their friends and families, we all lost the benefit of having them in our profession, of having them making the world a better place,” says Nicell. “We need to remember the individuals but also the lost potential. We can’t let this happen again.”

****

“I still find it almost impossible to believe that something like that could happen – that you could be targeted simply because you are a woman pursuing something you love,” says Curtis. “But if you look at where we are today, I think it speaks volumes. We remember these women and we honour them by pushing for change.”

****

Near the end of the interview, Curtis says she has always wanted to be an engineer. “I have great role models. My brother is doing his PhD in electrical engineering at U of T and her father came from a science background,” she says.

“When I was 7, he taught me how to change a tire because he said ‘you need to know how to do this and you can’t use the excuse that you’re a girl,’” she laughs. “He raised me to not be constrained by anything and to think of all the possibilities.”

Possibilities.