Veronica Strong-Boag is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, Professor Emerita in Social Justice and Educational Studies at UBC and Adjunct Professor in the Departments of History and Gender Studies at the University of Victoria. She has received the Tyrrell Medal in Canadian History from the Royal Society of Canada and numerous other prizes, including the Canada Prize in the Social Sciences and a Senior Killam Fellowship. She has served as president of the Canadian Historical Association and BC representative on the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Veronica Strong-Boag is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, Professor Emerita in Social Justice and Educational Studies at UBC and Adjunct Professor in the Departments of History and Gender Studies at the University of Victoria. She has received the Tyrrell Medal in Canadian History from the Royal Society of Canada and numerous other prizes, including the Canada Prize in the Social Sciences and a Senior Killam Fellowship. She has served as president of the Canadian Historical Association and BC representative on the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

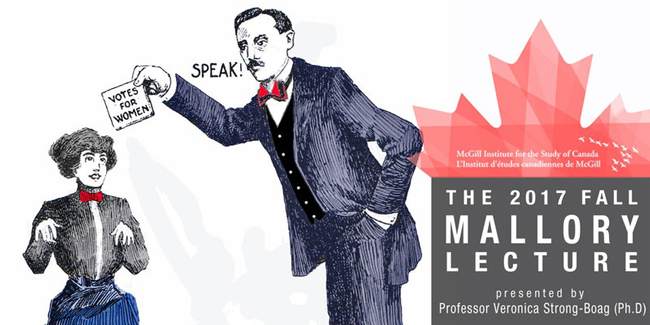

Strong-Boag’s latest book, The Last Suffragist Standing: The Life and Times of Laura Emma Marshall Jamieson, 1882-1964, will appear with UBC Press in 2018. She acts as the General Editor of the UBC Press series, Women Suffrage and the Struggle for Democracy; and as the director of the pro-democracy website, womensuffrage.org. Strong-Boag is also on the Editorial Board of Voices/Voix. On Nov. 1, she will present Where was Democracy? The Case of Woman Suffrage in Canada as the J.R. Mallory Lecture at McGill.

Strong-Boag recently spoke with the Reporter.

Why should Canadians know more about democracy?

In 2017, democracy is in trouble world-wide. A pervasive democratic deficit feeds and reflects commonplace alienation and despair as Canadians and others search for solutions to global tragedies.

But our problems did not emerge overnight. They are deeply rooted in history, from the dispossession of Indigenous peoples to patriarchy’s hard hold on governance of every type. Recognition of these roots will aid the search for remedies and reconciliation.

What does the forthcoming seven-volume series from UBC Press, Women Suffrage and the Struggle for Democracy, offer readers?

Above all, it explores the unappreciated richness of the suffrage story. The ‘great cause’ inspired a diverse crew of Canadian-born, immigrant, and visiting women and men, who made every region of the country distinctive.

Joan Sangster reminds readers of that diversity as she highlights socialist supporters across the country.

In Quebec, Denyse Baillargeon points to early Indigenous women voters, while Tarah Brookfield showcases the Black feminist abolitionist, Mary Ann Shadd Cary in Ontario.

Lara Campbell emphasizes the labour ties of B.C. activists while Sarah Carter explores the differences among the prairie provinces.

In Atlantic Canada, Heidi MacDonald discovers radicalism and ties to the U.K., and the final volume by Lianne Leddy will offer an unprecedented assessment of Indigenous women’s wide-ranging political struggles.

All the authors examine the anti-feminists and racists who were both some of Canada’s most powerful politicians and a wider intransigent community of opponents to equality.

In short, the series documents a bitter battle among different versions of what Canada ought to be. Democracy was only partially victorious. Indigenous and some Asian women remained excluded (as did men) for many years while opposition to the right of all women to political authority never disappeared. Today’s democratic deficit is one legacy.

Why have many scholarly and popular commentators seemed more preoccupied with the shortcomings of suffragists than with those of their anti-feminist and misogynist opponents?

This can be another form of victim-blaming or shaming, even as it deflects attention from continuing opposition to equality. Feminists get condemned for failures, whether of conscience or nerve, while defenders of masculine privilege creep by with little penalty. The latter’s offences frequently disappear from history. No wonder Canadian MPs were still able to laugh when Margaret Mitchell raised domestic violence in the House of Commons in 1982.

To put a positive slant on this unbalanced treatment: continuing criticism has contributed to modern feminism’s growing consciousness of racism and classism. Current political debates about terrorism and face- covering suggest that many Canadians similarly need to examine their consciences.

Which Quebec suffragist deserves more attention?

In fact, from the early Indigenous voters to more well-known figures like McGill’s professor of biology, Carrie Derick, and socialist social worker Rose Henderson, all are worth knowing a good deal better.

But, if I had to choose one, I’d recommend the extraordinary Idola Saint-Jean, a contemporary of the more prominent Thérèse Casgrain. Fortunately, recovery is now a great deal easier. This fall, Marie Lavigne and Michèle Stanton-Jean have published an important biography, Idola Saint-Jean, Insoumise with Boréal Press. It will be an early Christmas present to myself.

Where was Democracy? The Case of Woman Suffrage in Canada, Nov. 1, 5 to 7 p.m., McLennan Library Building (3459 McTavish), Colgate Seminar Room, 4th floor. This event is free and open to the public. As seating is limited, please register by email or on Eventbrite to secure your seat.

The lecture will be followed by a cocktail reception in the reading room, and will be accompanied by an exhibition to showcase the library’s holdings on women’s political activism and suffrage, as well as the holdings related to Professor Strong-Boag.