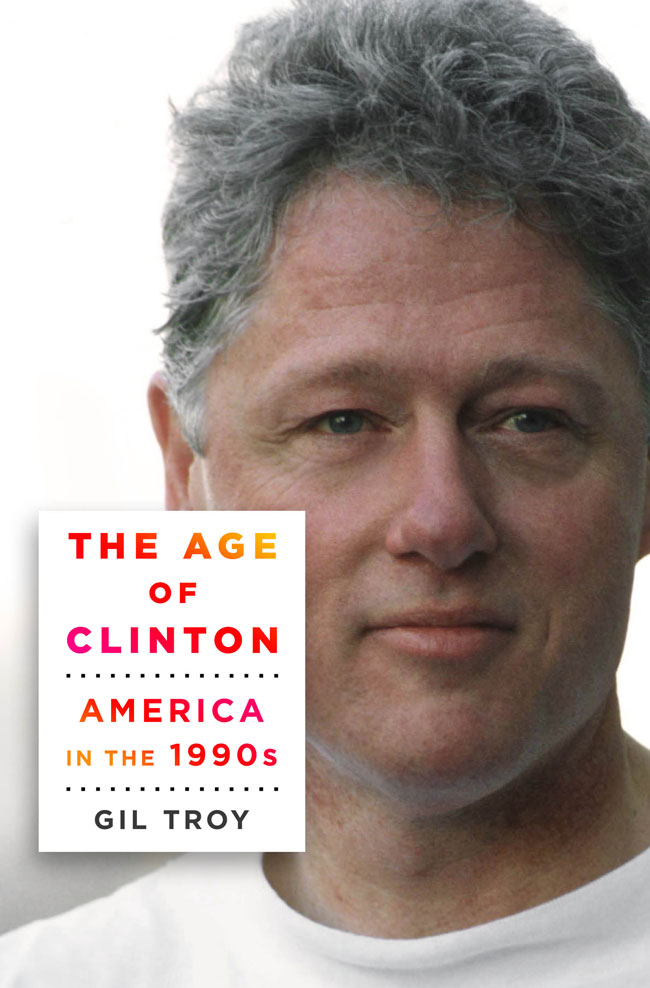

The finalists for the 2015, Cundill Prize in Historic Literature were announced earlier this month. The winner of the world’s most lucrative award for historical non-fiction writing will receive $75,000 US. Prior to the Nov. 2 gala, in which the winner will be announced, the three finalists (Sven Beckert, Susan Pedersen and Bettina Stangneth) will participate in roundtable event at the International Festival of Authors (IFOA) in Toronto on Oct. 31. McGill History Professor Gil Troy will moderate the discussion. Troy recently sat down with the Reporter to talk about the kinds of challenges writers like the Cundill finalists face, his own existential fears as an author and his new book, The Age of Clinton.

You will be moderating a discussion between this year’s Cundill Prize finalists on Oct. 31. As an author who has written many historical non-fiction books yourself, what are the biggest challenges involved?

In my writing, which includes the kind of sweeping books that the Cundill Prize likes to praise, I find that one of the biggest challenges is cutting, cutting and cutting. It is so much easier in the modern world, when we are awash in data, to write long, very long, far too long. The art of revising, the act of honing, the pain of abandoning beloved facts, anecdotes, and sentences, can be agonizing. My first draft of The Age of Clinton came in at about 200,000 words – by the time it was published, I had also added material but it was down to about 120,000.

A second, more existential challenge, is that fear, when you are writing, when it is published, even when you are promoting the book, that no one cares, that no one will pay attention, and that, rather than this being the noble, mission-driven, idea-rich project you imagined it could be, it’s just an indulgence that will be overlooked and underappreciated. My antidote to those feelings is that when I get my first copy of a book I’ve published in the mail, I sit down in my comfy chair, and read it from cover to cover. If I am satisfied, I remind myself how lucky I am to be able to have time to research and write books, and how extra lucky I am actually to get the darned thing published. I then think about two or three key ideas I hope to share with others from the book. I then hope that I am grateful and humble enough to overcome the predictable, forthcoming waves of authorial anxiety and frustration. (It also reminds me how lucky I am to have a wonderfully supportive institution like McGill behind me, and a super-supportive family. We often take such blessings for granted, and shouldn’t).

Your own book, The Age of Clinton: America in the 1990s, came out on Oct. 6. What are these next few months going to look like for you?

Just as the book came out, I began a semester-long stint as a visiting scholar at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank. I timed the book to coincide with Hillary Rodham Clinton’s (at the time) expected candidacy. I already have a number of events to promote the book lined up in various cities, so there will be lots of trains, planes, and automobiles. But most important, I am hoping to help the American public – or at least my handful of readers – take the Clintons seriously, thinking about what great successes and failures there were during the Clinton presidency. At the same time, the book is about the cultural, economic, technological and ideological changes of the 1990s too, with the Clintons as the key characters, so I am hoping to help others appreciate how transformational the 1990s were. Remember, back in 1990, the Soviet Union was united, Germany was divided, Amazon was just a river, Google was just a really big number, and “Pay Pal” was something loan sharks said. The 1990s in many ways invented our times, and we have much to learn from both the good and the bad of the times – and of the Clintons.

Just as the book came out, I began a semester-long stint as a visiting scholar at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank. I timed the book to coincide with Hillary Rodham Clinton’s (at the time) expected candidacy. I already have a number of events to promote the book lined up in various cities, so there will be lots of trains, planes, and automobiles. But most important, I am hoping to help the American public – or at least my handful of readers – take the Clintons seriously, thinking about what great successes and failures there were during the Clinton presidency. At the same time, the book is about the cultural, economic, technological and ideological changes of the 1990s too, with the Clintons as the key characters, so I am hoping to help others appreciate how transformational the 1990s were. Remember, back in 1990, the Soviet Union was united, Germany was divided, Amazon was just a river, Google was just a really big number, and “Pay Pal” was something loan sharks said. The 1990s in many ways invented our times, and we have much to learn from both the good and the bad of the times – and of the Clintons.

This isn’t the first book you have written about the Clintons. Hillary Clinton continues to run an intense campaign in a race that’s been full of surprises, from Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump. How can your book help us better understand what’s happening in the campaign?

While my book, as a work of history, cannot help us predict the future as to who will win, I think there are at least three takeaways that are relevant here. First, the book helps us appreciate both Clintons’ tremendous charisma and appeal to many, especially Baby Boomers, when they first were campaigning back in 1992. You see photos from the campaign and you are struck by how young and dynamic they were back then, and how much excitement Bill Clinton, in particular, generated. Second, the book notes how complicated Hillary Clinton’s position was then, especially as a powerful, independent, super-intelligent feminist forced to play the role of Southern belle and compliant political spouse – but we also see how adaptable she was and that one of the keys to her success was (and remains) her tremendous ability to learn from her mistakes. And third, the book helps us understand what seems to be a lot of the insanity of the current campaign, rooting it in the 1990s, when once “solid” America was becoming more “liquid,” more fluid, more open, more confused, more anxious, more flamboyant. In other words, what was once a Republic of Something – standing for key, anchoring traditional ideas – risks becoming a weightless confused Republic of Nothing, even as it becomes a more welcoming, open Republic of Everything. These are indeed challenging times, for leaders and the led!

Tell us what you are most looking forward to in terms of moderating the Cundill / IFOA event on Oct. 31.

Given that I understand more than most, how difficult it is to write these kinds of books, and how stressful it is to promote them, what I most want to do on October 31 is to celebrate these amazing authors, showcase their most exciting ideas, and delight in their impressive achievements. I hope that everyone at the event walks away with a nugget or two from each work as well as an overall appreciation of what the author tried to convey in the book.

More broadly, I want us all to appreciate the power of words, the lure of the life of the mind, and the delightful opportunity we have that afternoon, even in our high-tech age, to celebrate the old-fashioned act of publishing a book to conjure up a lost world, to advance an important argument, to teach, enlighten, and inspire the public.