Harnessing humidity to quench thirst in the world’s most arid regions

By Neale McDevitt and Chris Chipello

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that some 780 million people in the world today do not have access to clean drinking water. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, this lack of safe water has a serious impact on the lives of hundreds of millions of people. Women and girls especially bear the burden of walking miles at a time to gather water from streams and ponds – full of water-borne disease that often lead to serious illness and death for millions of people. WHO says that every year more than 3.4 million people die as a result of water-related diseases, making it the leading cause of disease and death around the world.

But what can be done – especially in poor, arid regions where people must contend with the dual challenges of poverty and drought? To paraphrase Bob Dylan, the answer may be blowing in the wind.

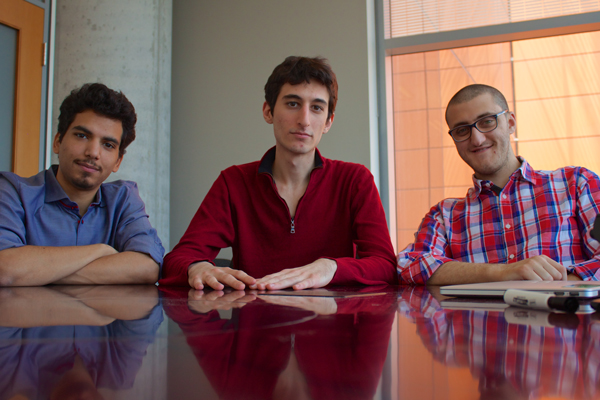

“Our idea is to use a large sail – 55 square metres – to harvest dew to use as drinking water,” says McGill student Sami Sayegh of the Skywell project developed by himself and Concordia students Al-Hurr Al-Dalli and Charles Gedeon. “Sails are relatively cheap and a sail of that size could collect about 110 litres of water a day which would make it a valuable water source for small communities.”

If you think the Skywell project sounds like a good idea, you aren’t alone. Sayegh, Al-Dalli and Gedeon are presently in Rotterdam, having just been named as winners of the global student competition Shell Ideas360.

The competition – which challenges university students to conceive, share and collaboratively develop innovative ideas to help tackle energy, water and food challenges around the world – kicked off in September 2013, and attracted almost 700 submissions. Sayegh and his teammates Al-Hurr Al-Dalli and Charles Gedeon (both from Concordia) have made it to the final round of five that also includes teams from Australia, India, Singapore and The Netherlands.

On May 14, Sayegh and his teammates stood before a panel of judges and pitched the Skywell project in the final phase of the contest. The winners were announced on May 15, with Sayegh and his teammates earning a once-in-a-lifetime expedition with National Geographic.

While Al-Dalli and Gedeon were instrumental in developing business aspects of the proposal and in creating the team’s video – an essential part of the competition – Sayegh was the person who conceived Skywell. He got his inspiration from nomadic people like the Bedouins who have used a similar technique for centuries to survive the challenges of life in the Sahara.

“I remembered hearing about the Bedouins when I was in second grade,” said Sayegh, who was born in Lebanon but grew up in the United Arab Emirates. “They used to place a tarp out at night, and in the morning a certain amount of water would be gathered in the form of dew. I figured if that could be done on a larger scale, maybe instead of a litre or two you could get hundreds of litres.”

Sayegh and his teammates say Skywell could work in many regions of the world that have appropriate conditions for dew formation, such as Australia, South Asia and the Far East, the Middle East, Africa, Central America and South America.When the sun rises each morning, humidity collects on the large sails and is directed into a reservoir where it is filtered so it can be consumed immediately or collected as a backup for dry periods.

The beauty of Skywell is in its simplicity. Because it is compact and has no moving parts, upkeep is minimal once the system is installed. “We estimate that one unit will cost about $800 – and we think this is on the high end,” says Sayegh. “The nice thing about the system is that once it is paid for it will continue to provide water without any further running cost. There’s initial investment and that’s it.”

On top of benefiting communities – the 110-litre daily output of water will answer the needs of approximately 60 people – Skywell will also be a boon to farmers in arid areas. “In that case, the farmers would have a big reservoir tank that collects water day after day and, should a drought happen, they could tap into that reserve for several weeks,” says Sayegh.

Having earned his Bachelors of Arts and Science last year (concentrating on biology, economics and social studies of medicine), Sayegh has just completed a year as a qualifying student in which he did graduate-level chemistry courses without being enrolled in a Masters program. He says he’s hoping to begin graduate studies next year, although the whole Skywell experience has expanded his horizons.

“One of the motivations for entering this competition was to see if I could open up doors to other avenues other than grad school because I also have this really strong urge to try something new,” says Sayegh. “If I could open a business or do something in this area that would also be very enticing.”

In Sayegh’s case, the sky’s the limit.