By Neale McDevitt

When asked how he was handling this winter’s abnormally long stretches of cold weather, Lyle Whyte chuckles “Actually, I was going to break out my high arctic winter jacket,” says the Canada Research Chair in Environmental Microbiology.

But, unlike many winter-weary Montrealers, Whyte isn’t one to complain about frigid climes, having conducted the bulk of his research up at McGill’s High Arctic Station for the past 14 years. In fact, his wealth of experience working in extreme cold temperatures recently helped him land a spot on an elite team of scientists handpicked by the European Space Agency (ESA) to work on the ambitious ExoMars 2018 project, specifically as a member of the Landing Site Selection Working Group (LSSWG).

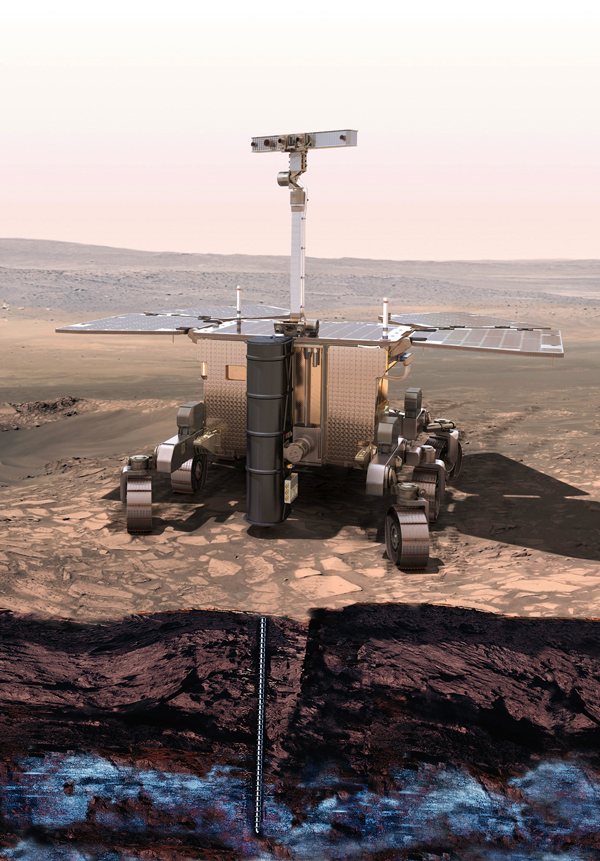

In 2018, ESA will launch a mission to Mars that will employ a Rover equipped with a comprehensive suite of instruments dedicated to geology and exobiology research on the Red Planet. In short, ExoMars is looking to help answer that age-old question; has life ever existed on Mars? But before the Rover can begin collecting its data, it has to overcome one major obstacle – landing.

“Landing on Mars is a pretty tough business,” says Whyte. “The little oval area that you can predict where this thing will land is about 100×20 kilometres. That spot must be a scientifically interesting so that we have a high chance of meeting the scientific objectives of the mission. But we also have to pick a spot doesn’t have a lot of cliffs or high hills and isn’t littered with boulders, because if [the landing craft] a large rock, the mission is over.”

Having put out a call for potential landing sites to members of the international scientific community, the ESA compiled a host of proposals until the end of February. Whyte and the other members of the LSSWG are currently reviewing each proposal in order to whittle the list down to a single site.

Once on Mars, a rover equipped with various tools will explore the surface. One of the tasks is to drill into the subsurface to collect core samples. The extreme Martian climate – very cold and very dry – makes drilling a huge challenge. Again, this is where Whyte’s expertise will come into play.

“I’ve spent a lot of time drilling in regions that are cold and dry,” he says. “With an extreme environment comes a whole new set of challenges. When you’re drilling into a permafrost of water, ice and frozen dirt, the rotating drill bit causes friction that can melt the ice. But, as soon as you stop spinning in a place like Mars or the high Arctic, it can freeze right away and you’re stuck. Doing it robotically only increases the difficulty.”

And what will the Rover discover on Mars? Who knows, but Whyte is excited at the prospect. “The most likely type of microorganism or microbial community that existed or may still exist on Mars will probably be organisms called cryophiles – microbes that I’ve done a lot of research on,” he says. “These are microorganisms that can live at subzero temperature and in very salty conditions – because the only way you can have liquid water in these temperatures is for it to have very high salt concentrations.”

Whyte will also help ExoMars comply with the protocols of planetary protection – a set of regulations that must be followed when ESA, NASA and any other space agency sends a spacecraft to another planetary body.

“We want to avoid forward contamination,” says Whyte. “There will be microorganisms from earth on the spaceships as they are on your telephone right now. We don’t want to contaminate Mars with earth’s microbes. So we must meet different levels of sterilization, which is both complicated and expensive.”

The challenge, Whyte says, is that many of the landing sites that are richest in data are also the hardest to gain official access to. “It’s a bit of a Catch-22 situation because there are certain places on Mars that we think have high probabilities of having bio signatures of ancient life or even existing microbial communities – but these sites are essentially off-limits,” says Whyte. “There’s an ongoing debate between people like myself who think we may be going a little bit overboard on this and missing out on important opportunities and other members of the scientific community who strongly believe that these operations should be completely sterile.

“We’re still four years away from launching, so I’m sure we’ll be able to come to a consensus,” he says. “The bottom line is that we all want the mission to be a success.”