Enkhe-Tuyaa Montgomery and Jack Theis are the latest recipients of the Rathlyn Fellowship. Sponsored by McGill’s Indigenous Studies Program, the $12,500 award supports Indigenous graduate students in their pursuit of excellence in research.

Montgomery, a third-year PhD candidate in anthropology, critiques current harm-reduction practices in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, advocating a holistic approach that goes beyond providing naloxone and sterile needles, to address deeper needs for housing, food and community.

Theis, a master’s student in history, explores his Métis and Anishinaabe heritage, tracing his Bottineau family’s migration and racialization within settler-colonial contexts.

Enkhe-Tuyaa Montgomery: A holistic approach to harm reduction

When politicians and legislators talk about cracking down on substance use in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, Enkhe-Tuyaa Montgomery shakes her head.

“This is not just a war on drugs,” said the researcher. “This a war on drug users. This is a war on the poor.”

Montgomery understands the challenges faced by the members of that community. As part of her research on harm reduction, Indigeneity and belonging in the Downtown Eastside, she works daily with people experiencing homelessness, poverty, mental illness and substance dependency.

“We aren’t addressing what this community truly wants or needs, in terms of responses to substance use,” she said. “More attention needs to be paid to upstream issues, such as stable housing, safe supply, and a sense of belonging in the city. Without these, harm-reduction services lose their full impact. I’m particularly interested in non-clinical, community-based harm reduction programs that prioritize people’s lived experiences over medical interventions.”

Montgomery works with the Coalition of Peers Dismantling the Drug War as well as the Eastside Illicit Drinkers Group for Education on non-clinical programs that emphasize community and peer support. Programs like the Drinker’s Lounge community-managed alcohol program provide safe spaces for people to have access to alcohol in a controlled, peer-run environment, highlighting the importance of belonging.

The Rathlyn Fellowship allows Montgomery, a mixed-race Siberian Buryat woman, to give back to the local community.

“The fellowship allows me to fairly compensate the people I work with for their time, knowledge and labour. As researchers, we have a responsibility to recognize and respectfully compensate community members’ contributions to research,” said Montgomery.

Montgomery said another part of her work is to push back on misconceptions about the Downtown Eastside.

“I’m honoured and humbled to be welcomed into this community and allowed to work here. The generosity, love, and care I’ve witnessed – and experienced myself – are unlike anything I’ve encountered in my life,” she said.

“In the face of forces that invite death, the people in the Downtown Eastside are summoning life.”

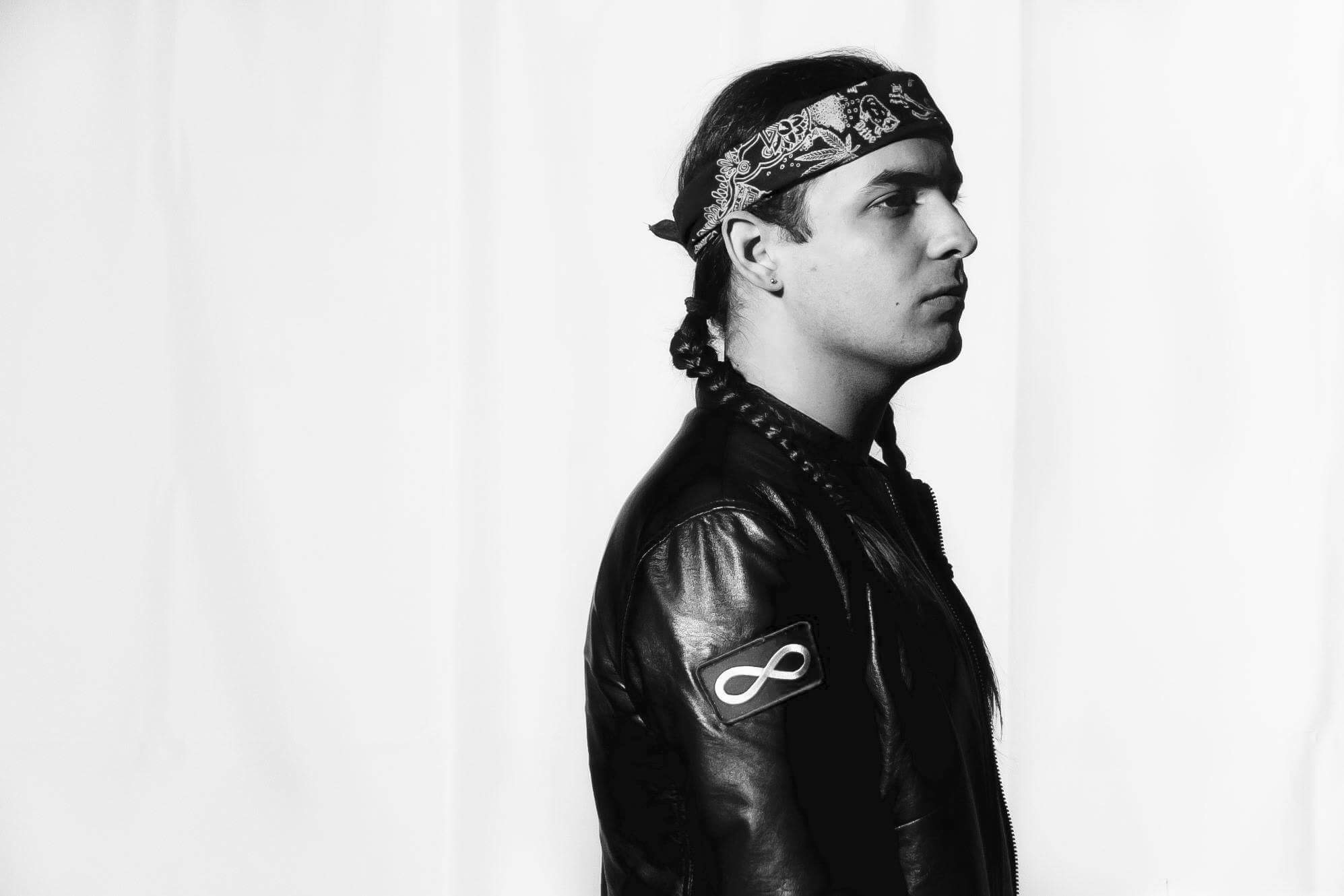

Jack Theis: Reclaiming family history

Writing a master’s thesis is a huge investment in time and energy. For Jack Theis, a history student, it is also deeply personal.

“I draw from my ancestors’ stories – ones I was raised on – to trace their journeys and understand how their ideas about community and belonging shifted over time, amid the competing fur trade companies in Red River in the 1810s and 1820s and eventually American expansion and accompanying assimilationist policies. Throughout this time, there was an emergence of new ideas about what it meant to be ‘Native,’ ideas that didn’t exist in my ancestors’ communities in the 1780s,” Theis said.

“Too often, people project Dances with Wolves fantasies onto my ancestors. These were real people with actual histories, not the exoticized versions some try to create,” he said.

Theis traces the Bottineau family’s migration from Red River of the North to the Chippewa Valley, analyzing historical sources to understand how they were racialized within the context of settler-colonialism and their multifaceted connection to both the Anishinaabe and Métis social worlds.

Theis was raised on a detailed genealogy – both oral and written – of his family, a genealogy that has been passed down since the 1800s.

But, aside from that history, he grew up “assimilated and completely disconnected” from his Anishinaabe and Métis communities.

Eventually, he reconnected with his communities in Minneapolis and Winnipeg. The more Theis learned about Anishinaabe and Métis cultures, histories and languages, the more he noticed inaccuracies in writings about his ancestors: errors made by relatives, scholars and amateur genealogists.

“I had to correct these errors, which led me to explore my ancestors’ views on Indigeneity and how they navigated concepts like blood quantum and settler-colonial ideas of who was considered Native,” he said. “With my research and writing, I’m trying to help my people fight back against colonialism by reclaiming ancestral forms of community belonging.

“I’m also trying to complicate the Anishinaabe-Métis binary in Canada by shedding light on the ways that we have been historically and inextricably tied to each other in the U.S.,” he said.

Theis said reconnecting with his Anishinaabe and Métis communities has had a big impact on his life.

“It’s been a difficult journey at times, but the experiences and relationships I’ve gained have been incredible. Now that I’m part of this community, I can’t leave,” he said.